Roots Rock Rebel

"There ain't no better blend / Than Joe Ely and his Texas Men"

Joe and Sharon Ely got in touch in the summer of 2020. They were working to put out the previously unheard, but underground-famous, recording of Joe and the Clash in concert.

The show was the product of an unlikely match made in rock n roll heaven. A West Texas high plains honky-tonk troubadour and a U.K. punk band transcendent of punk, time and place on the cusp of international stardom. The Clash and Ely were each authentic, the real thing, honest to themselves, striving for something beyond what was popular, trying to get to what was essential.

Joe told me that one of the first times he played London he walked into his dressing room to find the Clash there, waiting to pay homage to this roots-American rock n roll hero of theirs. Hanging out, asking him questions about Texas, country music, Buddy Holly, Sonny Curtis. Bugging him, if he was honest about it. He didn’t know who the Clash was, didn’t realize then how big they were. Shabby vagrants with funny haircuts. He would have laughed if someone had told him that they were “the only band that matters.”

No matter the dressing room bust of their first meeting, they became fast friends, traveling and touring together, singing on each other’s albums. Ely told me that he was at the Combat Rock sessions and sang backup when they recorded “Should I Stay or Should I Go”. He and engineer Eddie Garcia provided the Spanish translation sung in the second verse (“Si no me quieres, librarme!”) and it was Ely, with Strummer, who snuck up on Mick Jones as he was recording the lead vocals, scaring the shit out of him right before he says “split!” in the middle of the song (I guess that’s what all the yelling is about).

If the Clash and Ely started from a different place, they shared a common destination… and they brought us along with them. Their albums and shows were a direct connection to the roots of rock n roll, their songs powerful revelations about the strange joy and sorrow of being alive, really alive.

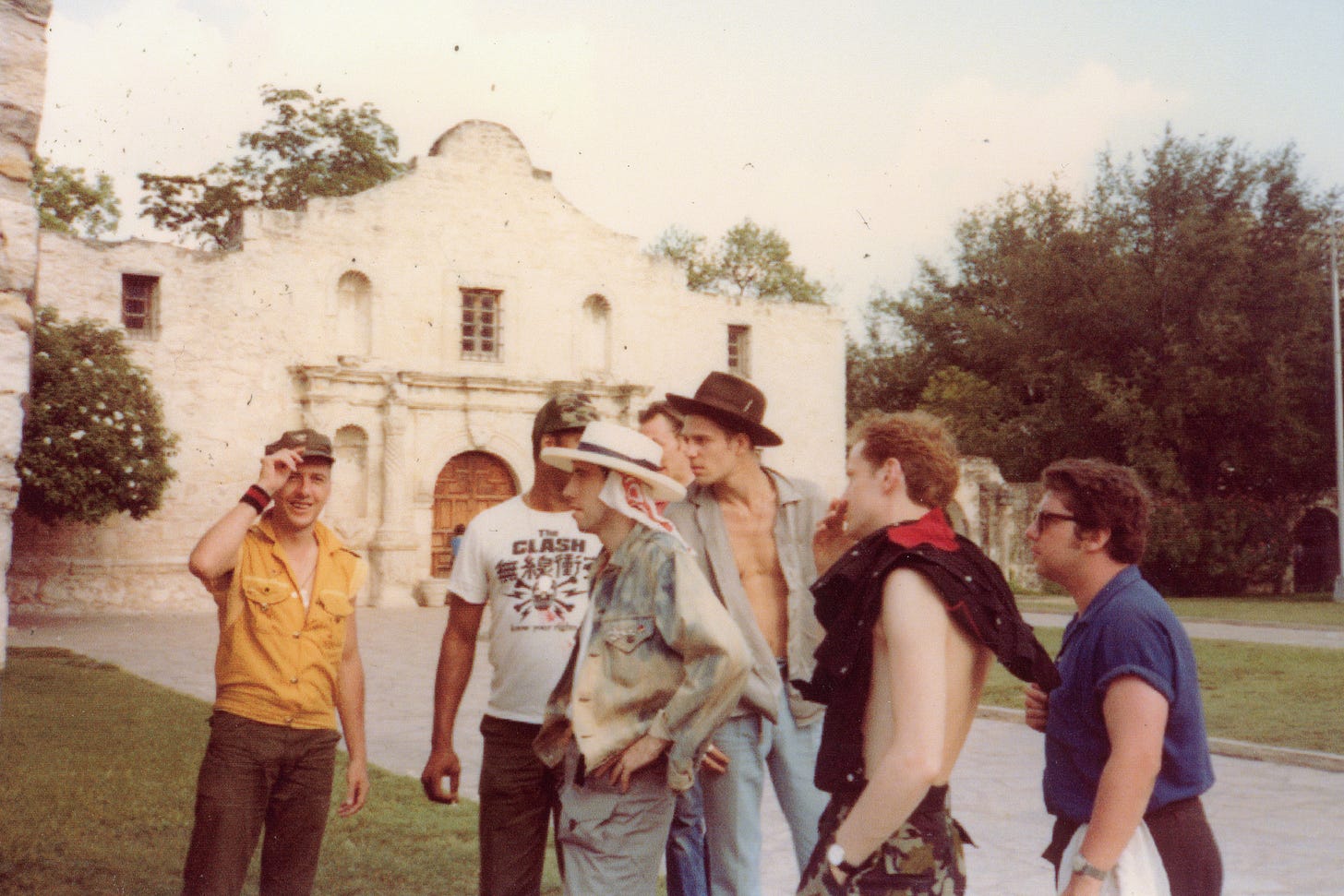

Ely brought the Clash to Texas, to his hometown of Lubbock and to El Paso too. The Clash, for their part, took him on tour in England and Europe as they were blowing up in the wake of London Calling.

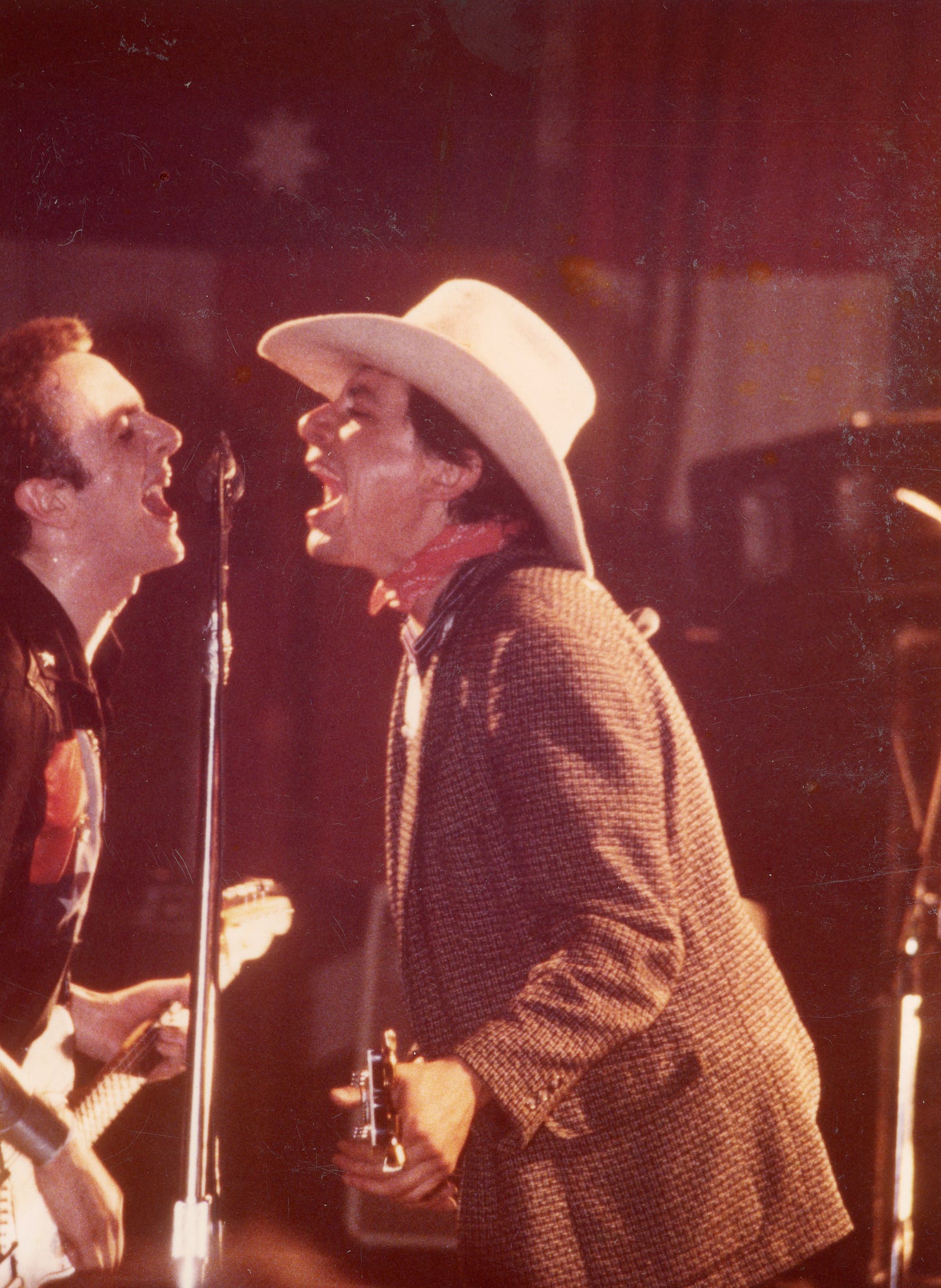

One night in early 1980, when Joe Ely and his band were playing London’s Hope and Anchor, Mick Jones and Joe Strummer, unannounced, joined him on stage. Fortunately, the Rolling Stones’ mobile unit was recording the show, in practice for a live-album recording taking place the following night (later released as “Live Shots”).

It was this impromptu recording of Ely and the Clash that Joe and Sharon wanted to release, with the proceeds going to Texas food banks, which at the time were struggling to meet the demands of Texas families in the midst of the pandemic.

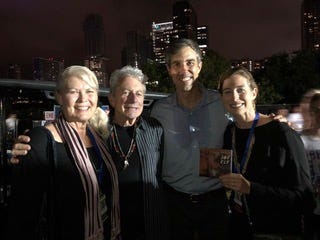

They asked if I’d write the liner notes to the record. We’d met in the 2018 Senate race when Ely joined an all-star lineup at Auditorium Shores in Austin in support of our campaign, and we’d stayed in touch since then. Sharon and Joe knew I was a huge fan of theirs and a huge fan of the Clash, so why not?

In preparation, I spent a lot of time on the phone with Joe and Sharon asking all sorts of questions, like, when you brought the Clash to Texas how did people respond? “In Lubbock, it scared people to death. They’d never seen anything like that before, and they didn’t know what to do. Maybe a couple hundred people in a small club.” Sharon told me that after their show in El Paso, they went to Juárez, where Ely and Strummer sat in with the bands in the bars and played every song they knew.

I asked Joe about punk rock, what he thought of it, where it came from. He talked about rockabilly, and always being in a band from 13 or 14 on, “always playing things that attached to Buddy Holly in some way.” By high school, he started to write more for the show, got fascinated by the songwriters, started to hitchhike for a few years, and started to write stuff. Dylan, Corso, Ginsberg, all got him.

What about “I Fought the Law”, written by Ely’s fellow West Texan Sonny Curtis and covered by the Clash in 1977? Joe told me it was the “first real political rock n roll song” – and that they played it that night at Hope and Anchor “at breakneck speed!”

Sharon talked about the heat and energy at Hope and Anchor that February night, the people packed in, the air dense, “full of human breath and so smokey, you could hardly see. Butch Hancock, who never smokes cigarettes, was smoking one.” She told me her glasses fogged up as soon as she walked in.

“The crowd,” she said, “was a pulsating heart.”

They sent me the recordings. I listened to them again and again, not able to believe my luck. They’re really that good. But as it turned out, the Clash’s label wouldn’t/couldn’t/didn’t sign off on the album’s release. Bummed that the world wouldn’t be hearing it anytime soon, I shelved the notes, hoping for another time, another way.

When I learned that Joe Ely passed away this week, I thought I’d break them out. Maybe sharing my reaction to this music helps in some small way to increase the pressure to get it out into the wider world. Because everyone should be able to hear these songs, hear these true rock n roll spirits playing their hearts out to the crowd at Hope and Anchor in 1980, playing to you and me wherever we are today.

Rest in peace, Joe Ely. And thank you Sharon for sharing him with us for so many years.

The Joe Ely / Clash Tapes:

That February night in 1980 in the basement of London’s Hope & Anchor they were following the roots of rock n roll, deep down to the source, and then all the way back up to what was new again.

At the time, however, Joe Ely and his band were just getting ready to play through a quiet rehearsal and sound check for a show taking place later that week. On a whim, Joe Strummer and Mick Jones were invited to join in, and word quickly spread through London that an impromptu show featuring Ely and the Clash was about to start.

They had met in 1977 when Joe Ely first came to London, The Clash big fans of his and Joe not even knowing who they were. Nonetheless, they’d become fast friends, traveling together and sharing the bill in clubs throughout England and Texas.

Ely invited them back home to Lubbock and to El Paso, West Texas towns where the spirits of Buddy Holly and Bobby Fuller were still strong. He took them across the border to Ciudad Juárez. Ely and the Clash would play for hours with the trios and mariachis, learning their ballads, corridos and rancheras, bringing in their own tradition of American roots rock, music overcoming borders and language.

The time in West Texas and the border would leave an impression on the Clash and Strummer, who would sing on “If Music Could Talk,”

Well there ain’t no better blend

Than Joe Ely and his Texas Men

Where the wind blows

I ain’t seen none like that scenery

(Sonny Curtis, when asked about how he came up with “I Fought the Law,” which both El Paso’s Bobby Fuller and the Clash would make famous, said “I wrote it in my living room in West Texas one sandstormy afternoon. If you know West Texas, the sand blows out there.”)

Now they were in London again, Ely about to play through his set, Strummer and Jones sitting in with the band, the place now packed. I’m sure they didn’t think of it this way, but I look back at it from 40 years in the future and I see Joe Ely and The Clash standing on that basement stage, saving rock n roll.

You hear it in their respectful rendition of Tampa Red’s 1940 classic “Don’t You Lie to Me” and Hank Williams’ “Honky Tonkin’” from 1948. Gene Vincent and Jerry Lee Lewis are there too. And then Sonny Curtis’ 1959 “I Fought the Law” comes barreling through at breakneck, threatening to blow the bolts off the drums (which actually break down later in the set). It sounds like Strummer, Jones, Ely and the band are just barely able to keep up with each other, like they’ve caught the wild outlaw spirit in that West Texas wind and are holding on for dear life.

But it’s the Clash and Ely’s originals that make this record transcendent, set as they are on this brilliant background of past masters. “Jimmy Jazz” with a chugging accordion and masterful lap steel, instead of the horns found on the studio version, rivals the original on London Calling. Strummer’s character seems somehow more dangerous, desperate and careless all at once, as he’s hounded by the lap steel police siren. And Ely’s “Fingernails” is just on fire. The energy is manic, Ely driving the song harder and faster than you think it can possibly go. Listen to Mick Jones absolutely shred the first two solos, followed by Lloyd Maines on lap steel (as if it couldn’t get any more intense, you can hear Lloyd yelling a note-for-note doubling of his steel solo near the end, a trick he learned at the Cotton Club in Lubbock).

It’s a window on to the crossroads of rock n roll in 1980. The players that night would go on to shape each other’s approach to music, and the way that we approach and hear rock n roll today. There’s a reason that the Clash were described as the “only band that matters”, and a reason that Joe Ely became one of the musicians and songwriters that band admired most. You can hear it on this record.

You can also see it in pictures and videos from that time, in their swagger, their clothes and hair, their rockabilly sensibility and their embrace of the country, blues and border roots of West Texas rock n roll. And you can literally hear it on Combat Rock when Joe Ely sings the Spanish background vocals on “Should I Stay or Should I Go.” It’s probably no accident that soon after the Clash broke up, bass player Paul Simonon rode his motorcycle across America until he got to El Paso where he stopped and made his home for a while

Ely and Strummer grew even closer post-Clash, and Ely’s presence is strongly felt in Strummer’s later work with the Mescaleros. When Strummer sings “Playing in the arroyos/Where the American rivers flow” on the posthumously released “Long Shadow”, he’s tipping his hat to Ely and connecting the desert gullies I played in as a kid to the larger American story he’s telling.

As a freshman at El Paso High, I couldn’t wait to leave West Texas, get out and see the rest of the world. The Clash records a friend lent me that year only stoked my wanderlust and desire to find those rare places that could have inspired a masterpiece like London Calling. How ironic that these punks from England had found it, in part, in Joe Ely and Bobby Fuller and the blowing winds of the Chihuahuan desert that I was so ready to leave. I had to go all the way to blighty to see the beauty that was right in front of me.

Wonderful read. Beto is such a good writer.

Love this so much!